THE reason why we call those aromatic, juicy, slightly shrivelled, winter-bearing globes “passionfruit” has nothing to do with the exciting, mouth-watering sweetness they generate.

European missionaries in 1700 often used the unusual flower divisions to illustrate the five wounds inflicted during the crucifixion or “Passion” of Christ when bringing Christianity to South America.

There are many types of passion vines grown, some for purely ornamental purposes, mainly in warm, frost-free regions.

The grafted black passionfruit Nelly Kelly is by far the hardiest and most reliable.

It easily withstands light frosts and is suitable for all but the frostiest parts of NSW, Victoria and Tasmania.

The yellow-fruited form, often mistakenly offered for sale even in cold districts, is often just a seedling.

It is frost-tender and, although growing strongly if planted in late spring, rarely survives the first cold winter, clearly preferring the subtropics.

All passionfruit vines detest heavy clay but thrive in perfectly drained soils enriched with organic fertilisers and manures.

Well-grown vines make outstanding privacy screens and can be grown against typical paling fences with a bolted-on trellis to add extra height.

They not only form dense screens and look great, but rarely offend neighbours because both sides usually get access to the luscious fruit.

Passion vines need bright sunlight and resent too much shade, especially early in the day. This is the most common reason for failure to flower and bear fruit.

In cool districts, plants are best grown against sunny, sheltered walls which act as heat-banks.

Open, wire trellises through which cold winds blow are always a problem in windy or coastal regions, where they remain stunted and have short lives.

The best time to plant passionfruit vines in frost-prone regions is late October or when safe to do so.

Prepare the planting area thoroughly because passionfruit vines are greedy feeders.

Deeply fork in a couple of bags of well-decayed cow or sheep manure for 4sq m around where each vine is to be planted.

Add a bucket of pelletised poultry manure and a good sprinkling of blood and bone, then deeply water and leave to settle and mature for a few days.

When buying grafted passionfruit plants such as Nelly Kelly, check for signs of suckering and pinch off any suspicious buds below the graft union.

Once suckers from the aggressive root-stock sprout they quickly take over. It is normal to see these alien shoots appearing metres away and they are hard to control — even if kept cut back.

When planting, avoid disturbing the brittle roots and place in the hole so the top of the root ball is level with the surrounding soil.

Burying lower stems causes lower bark to rot, always causing an entire plant to collapse.

A straw mulch, laced with blood and bone and a fistful of sulphate of potash spread over the surface will reduce moisture loss, but keep it clear of the main stem.

During hot, dry periods, keep the root-zone continually moist.

Never dig around passionfruit vines or even cultivate the soil near the roots. Damaged roots usually sucker from the point of injury, which is often the beginning of the end of most vines.

Pruning helps lengthen the life of vines and is first carried out during November about three years after planting.

Use hedge shears to clip off or thin out dead, congested, loose growth, always leaving main arms or branches intact.

Water heavily after each annual pruning to stimulate healthy growth and to promote bigger yields the following autumn and winter.

Most passionfruit vines have a relatively short life, usually about six or seven years unless carefully pruned. When yields start to fall and fruit becomes virus infected and woody, it’s time to grub out an old passionfruit vine and plant a new, healthy one.

Luckily the same spot can be used, but all old roots must be removed. Be sure to revitalise and re-enrich the soil before planting.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

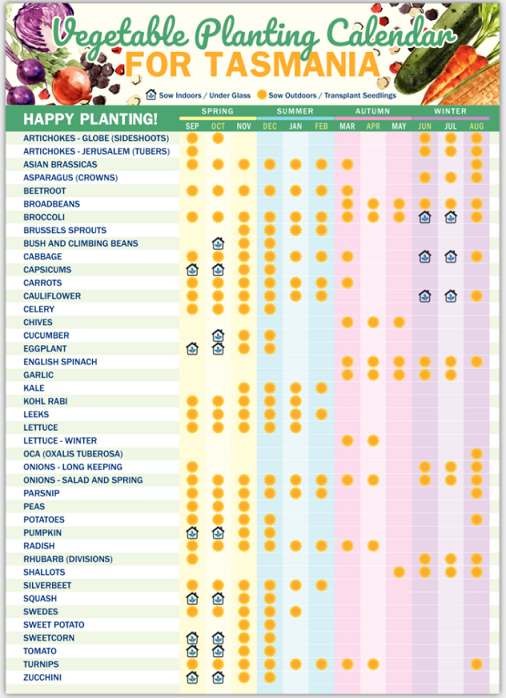

Check out our Tasmanian Planting Calendar Fridge Magnet – A5 size only

A year-round guide for when to plant your veggies in Tasmania. Never lose your planting guide again with a convenient fridge magnet for secure attachment to any metal surface. This growing guide has been tried and tested by some of the best Gardener’s in Tasmania, and is specifically adapted to the Tasmanian climate.

Excellent Gift for any Tasmanian you know with green thumbs and who likes Peter Cundall as much as i do!

Make sure you follow the calendar and you will have a successful year of growing vegetables in Tasmania.

Price includes FREE SHIPPING Australia wide. BUY HERE